Broker analysis links deepening divisions to growing violence and policy unpredictability in democracies across the globe.

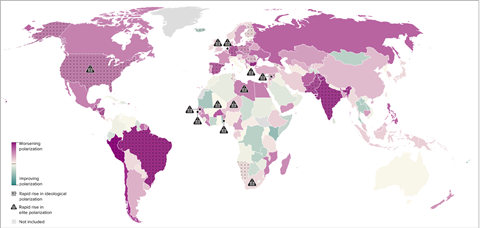

Political polarisation is deepening globally and fuelling instability, according to a new report from Willis.

The findings highlight growing challenges for businesses operating in increasingly divided societies, with potential consequences ranging from regulatory volatility to civil unrest, the broker emphasised.

Published on 25 June, the latest edition of the Willis Political Risk Index focuses on polarisation and its impact on political violence and governance.

Drawing on over a century of data across 200 countries, the report identifies a sharp rise in affective polarisation — the degree to which people view political opponents as enemies — particularly in democratic nations.

“Polarisation is not just playing out in national elections or media narratives,” said Sam Wilkin, director of political risk analytics at Willis.

“It’s affecting how individuals relate to friends, family and colleagues. There is a well-established correlation between polarisation and political violence. But businesses are also being drawn into these tensions in more personal and pervasive ways.”

According to the report, affective polarisation is now at its highest recorded global average.

While countries experiencing violent political conflict remain the most polarised overall, democracies such as the US, Germany, India, Brazil and Bulgaria have seen the fastest increases in recent years.

The US stands out as the only country where all three forms of polarisation — affective, ideological and elite — have intensified sharply over the past 15 years.

Ideological polarisation relates to divisions over policy issues, while elite polarisation measures the extent to which political leaders view one another as legitimate opponents.

Willis found that spikes in polarisation in democracies often follow major corruption scandals or economic shocks, which can undermine public trust in mainstream politicians. These conditions have also tended to foster populist movements and an uptick in political violence events.

The report also points to several structural factors that drive polarisation, including political competition along ethnic or religious lines, the influence of long-serving or populist leaders, and tensions over foreign policy. Polarisation is increasing both in mature democracies and in emerging markets.

However, the research offers some grounds for optimism. Historical examples suggest that cross-party coalitions, reconciliation processes and transparent responses to crises can quickly reduce levels of polarisation.

“Lessons from the past show that polarisation is not irreversible,” Wilkin said. “There are ways to address the root causes and rebuild trust, but it takes political will and a commitment to inclusive governance.”

The full report is available to download from Willis.

No comments yet